ArticlesFebruary 15th, 2026

Going Analog: What Paper Surveys Taught Us About Inclusive Community Engagement

When Darebin City Council asked us to lead engagement for their Cultural Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan, we had to think carefully about how to reach the communities the plan was actually for. Darebin is one of Melbourne's most culturally diverse municipalities — more than half of residents are born overseas, and about 15% don't speak English well or at all. Running traditional digital engagement – online surveys or through engagement platform – was not going to work.

We designed a detailed mixed-method engagement plan which including an online and paper-based survey. We translated our survey into six languages, printed hundreds of copies, and placed them in neighbourhood houses, cultural centres, libraries, and community hubs across the LGA. Of 230 total responses, 151 — nearly two-thirds — came back on paper. The paper respondents were demographically different from the online respondents, and what they told us shaped the direction of the whole project.

The engagement gap

Previous consultations in Darebin had struggled to hear from the communities most affected by inclusion policies — recent arrivals, refugees, public housing residents, and people with limited English. These are the people an inclusion action plan most needs input from, and they were consistently underrepresented.

This is common across local government. Community consultation tends to default to digital — online surveys, council websites, social media. These channels are efficient and easy to analyse, and they take fewer resources to manage, but they're biased toward people with reliable internet access, strong English, and familiarity with government consultations and platforms. A lot of voices get left out.

We designed a multi-method approach: a multilingual survey, interviews with community members and stakeholders, a community workshop with 30 participants, five advisory committee sessions, and elder consultations with the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation. The paper surveys were one of the most significant parts.

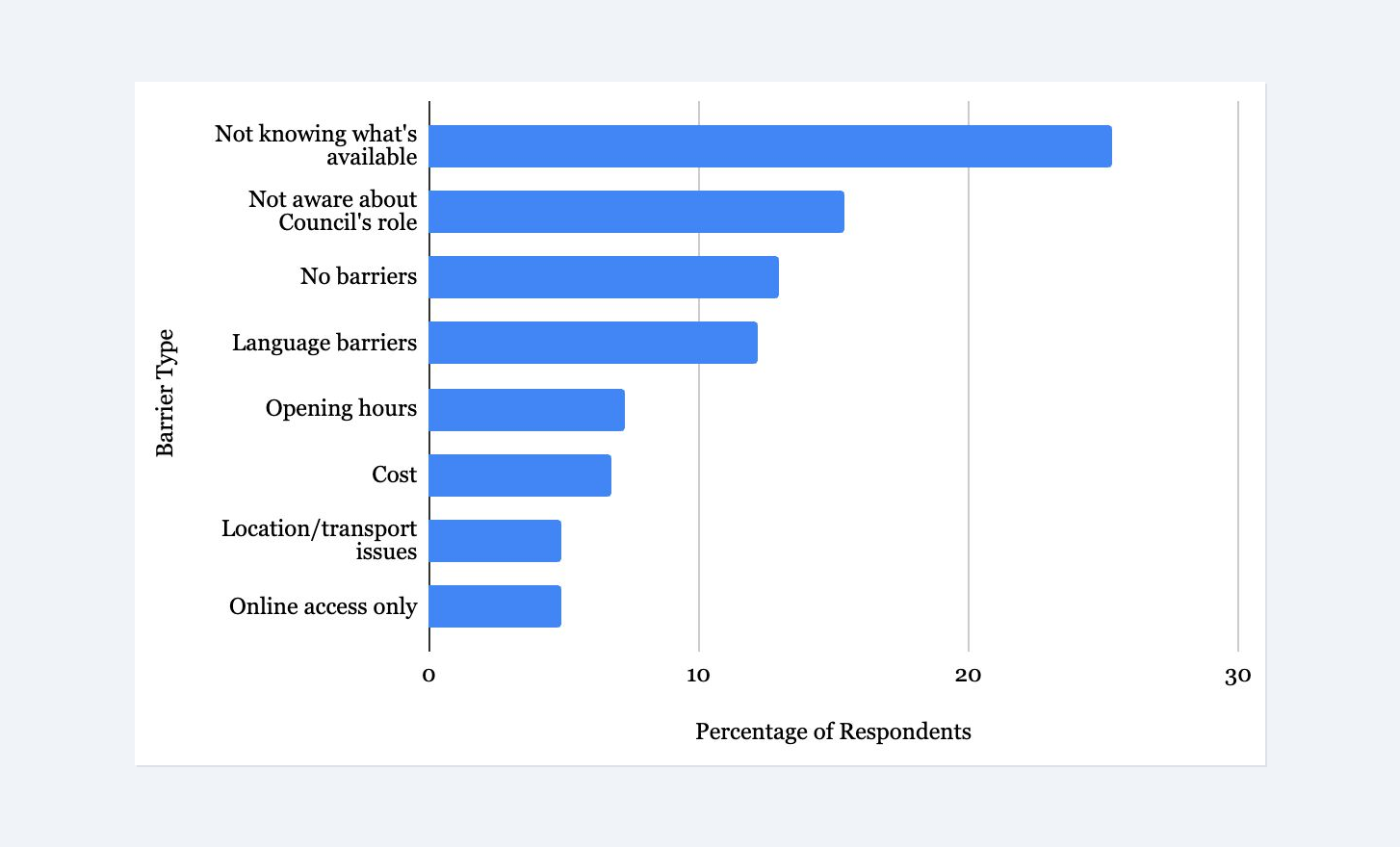

Information gaps are the biggest barrier to accessing Council services — 'not knowing what's available' alone accounts for 25% of all barriers reported, ahead of language, cost, and transport combined.

Going to where people already are

Instead of just publishing a survey online and hoping people would find it, we went to the places Darebin's CALD communities already spend time. We translated the survey into six community languages and distributed copies to neighbourhood houses, cultural centres, libraries, refugee housing, and Council hubs. Staff at each location helped explain the survey and supported residents to complete it.

Of 230 total responses, 151 came from paper and just 79 from the online version. The paper surveys reached older residents, people with limited English, those in public housing (10.9% of respondents), and residents without reliable internet access. The full case study has the detailed breakdown.

Processing handwritten surveys in six languages

Paper surveys create a practical problem that digital-first teams don't usually have to deal with: data processing. We had 151 handwritten responses in six languages. Manual data entry wasn't realistic at that volume.

We built custom OCR software to scan and extract responses from the completed forms. It handles multiple scripts and writing directions (supporting Arabic, which was one of our languages), converting handwritten multilingual responses into structured data.

The tool isn't specific to this project — we can offer multilingual paper survey processing to other councils and organisations running community engagement, which removes a real practical barrier to using paper at scale.

What the paper data showed

The 151 paper respondents were different people from those who responded online, and they reported different experiences.

Limited English speakers reported the lowest 'belonging' scores — 46.7% felt they belonged in the community, compared to 64.7% for native speakers. They were overwhelmingly reached through paper. Public housing residents faced the highest discrimination rates (48% having experienced some form of discrimination in the prior 12 months) but also reported the strongest sense of belonging (71.4%), due to the social supports available in public housing. They appeared in our data because we distributed surveys in their housing complexes.

Without the paper surveys, we wouldn't have seen these patterns. The communities experiencing the most exclusion often have strong local connections — they're not isolated from each other, but from government platforms. Our paper surveys reached them where they already were, and their responses shaped the direction of the action plan.

We've written about this before in our BRIDGE Framework: genuine participation means meeting communities on their terms, not expecting them to come to yours.

What this means for engagement practice

If you're running community consultation for a council or government department, it's worth asking what your current methods are missing. In Darebin, digital-only consultation would have only captured about a third of the responses we got.

Online surveys work well for the people they reach — they're efficient and straightforward to analyse. The issue is who they don't reach, and that gap tends to follow predictable lines: limited digital access, limited English, limited trust in government platforms.

Going physical from the start, rather than as an afterthought, is the most direct way to address this. Investing in translation means people can respond in their own language. And building infrastructure to process multilingual paper responses — rather than solving it from scratch each time — makes the approach sustainable.

The full Darebin case study covers the complete engagement approach and outcomes.