RMIT Centre for Innovative Justice

Supporting people with disability in the criminal justice system

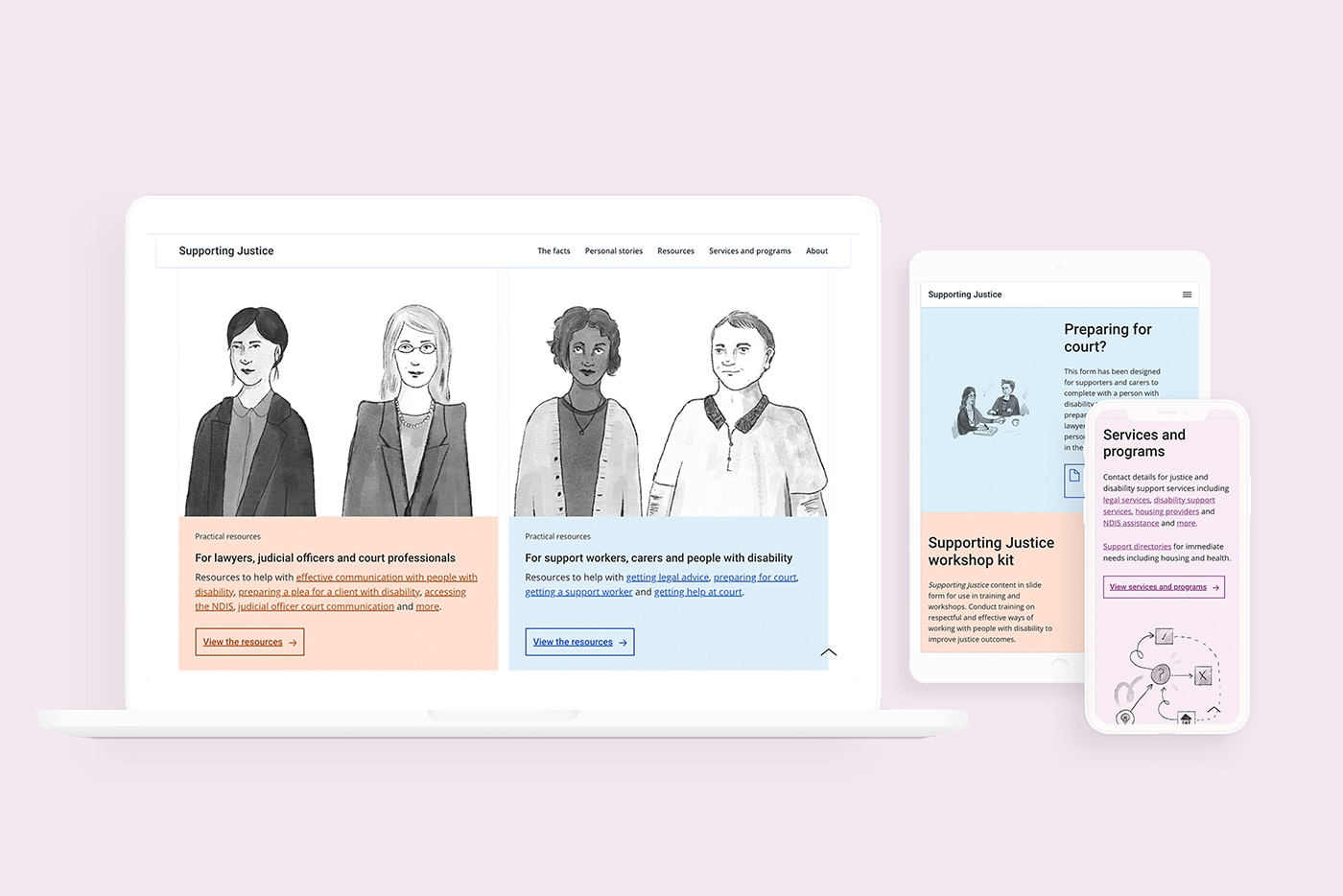

We partnered with RMIT’s Centre for Innovative Justice (CIJ) to create Supporting Justice, a resource to fundamentally change how people with disability are treated and supported in the criminal justice system, through inclusive collaboration, capability resource building, and accessible information design.

Outcomes

-

Developed accessible documents with and for people with disability to convey their legal and support needs clearly

-

Developed capability-building materials to improve recognition of signs of disability, and use of support and referral pathways

-

Co-created resource concepts with people with lived experience, legal professionals and judicial officers

-

Embedded human rights based principles in the design process

Services

- Social innovation

- Systems mapping

- Co-design

- UX and UI design

Disability rights in the spotlight

With the establishment of the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability in April 2019, the spotlight is on how we as a society better respect, recognise and support people with disabilities across all aspects of community life.

People with mental ill health and cognitive impairments (“people with disability”) are significantly overrepresented in the Victorian criminal justice system. For example, 2011 research estimated that 42% of male and 33% of female prisoners have an Acquired Brain Injury (ABI). Lack of appropriate supports for people with disability, coupled with stigma and discrimination, perpetuate cycles of disadvantage and lead to increased contact with the criminal justice system.

A prior related 2017 CIJ project, ‘Enabling Justice’, focused on the justice experience of those with ABI. It found that supported people with disability receive less harsh and restrictive sentencing. Unfortunately, the reality for many is that a lack of supported accommodation and transitional housing, and issues with eligibility for mental health and disability services, leads to repeated contact with police and in many cases, recurring sentencing and time in prison.

Designing the change

In 2018 CIJ approached Paper Giant for systems and human-centred design expertise to create an online resource for legal and court professionals to:

- improve outcomes for people with disability in the Victorian criminal justice system by working with them to protect and promote their rights

- increase the capability of the criminal justice system to work with people with disability

To achieve this, over 10 months in partnership with CIJ we combined systems and design-led approaches to:

- work with people with lived experience and representatives from Police, Corrections, Courts, private and public legal services, advocacy and peer support services and government agencies to develop a shared understanding of the experiences of people with disability in contact with the criminal justice system

- identify priority areas for change, and strategies to bring about these changes

- develop an accessible document with and for people with disability

- develop capability-building materials with and for legal and court professionals

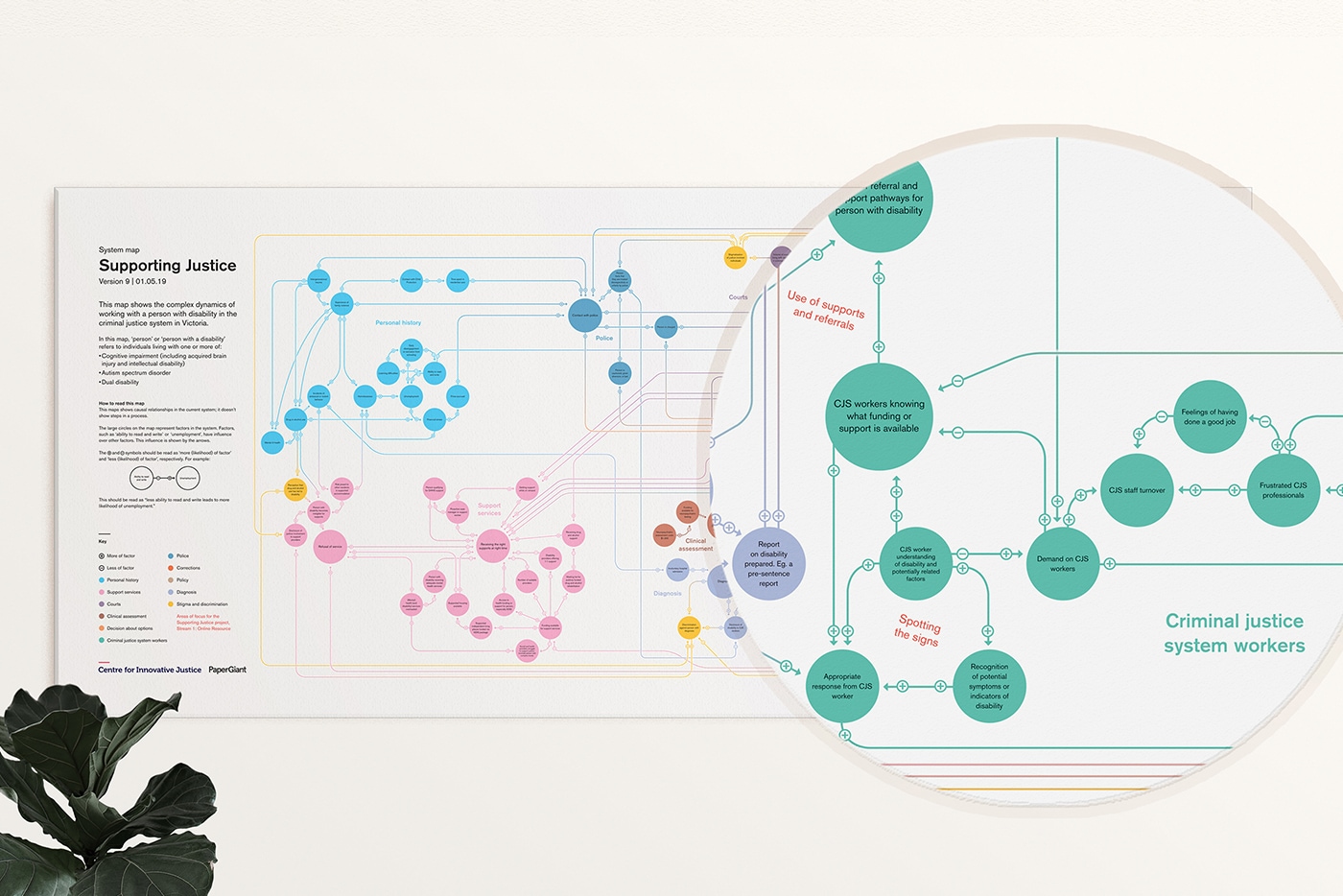

Understanding the system, visualising complexity

Before we could begin the work, we needed to build a shared understanding of the system and its complexities, and where it was failing for people with disability.

To do this we developed a system map to show how different parts of the criminal justice system and broader systems interconnect and impact on the justice and support outcomes of people with disability.

The system map validated justice stakeholder understandings of where things are breaking down, due to services being delivered by different people across the network. The map also confirmed understandings that frontline support workers lack their own support systems in the background, and that this compromises their ability to support people with disability appropriately and effectively.

The system map continues to serve as a powerful storytelling tool for getting justice stakeholders to see the big picture of what happens to people with disability in the criminal justice system and to see where they can take responsibility for making change in the context of other services.

...the map (gave me) a great appreciation and empathy for all the people who are actually a part of that system... the professionals and staff, in their own job... how difficult their own work is made because of the system.

— Peer support worker and person with lived experience

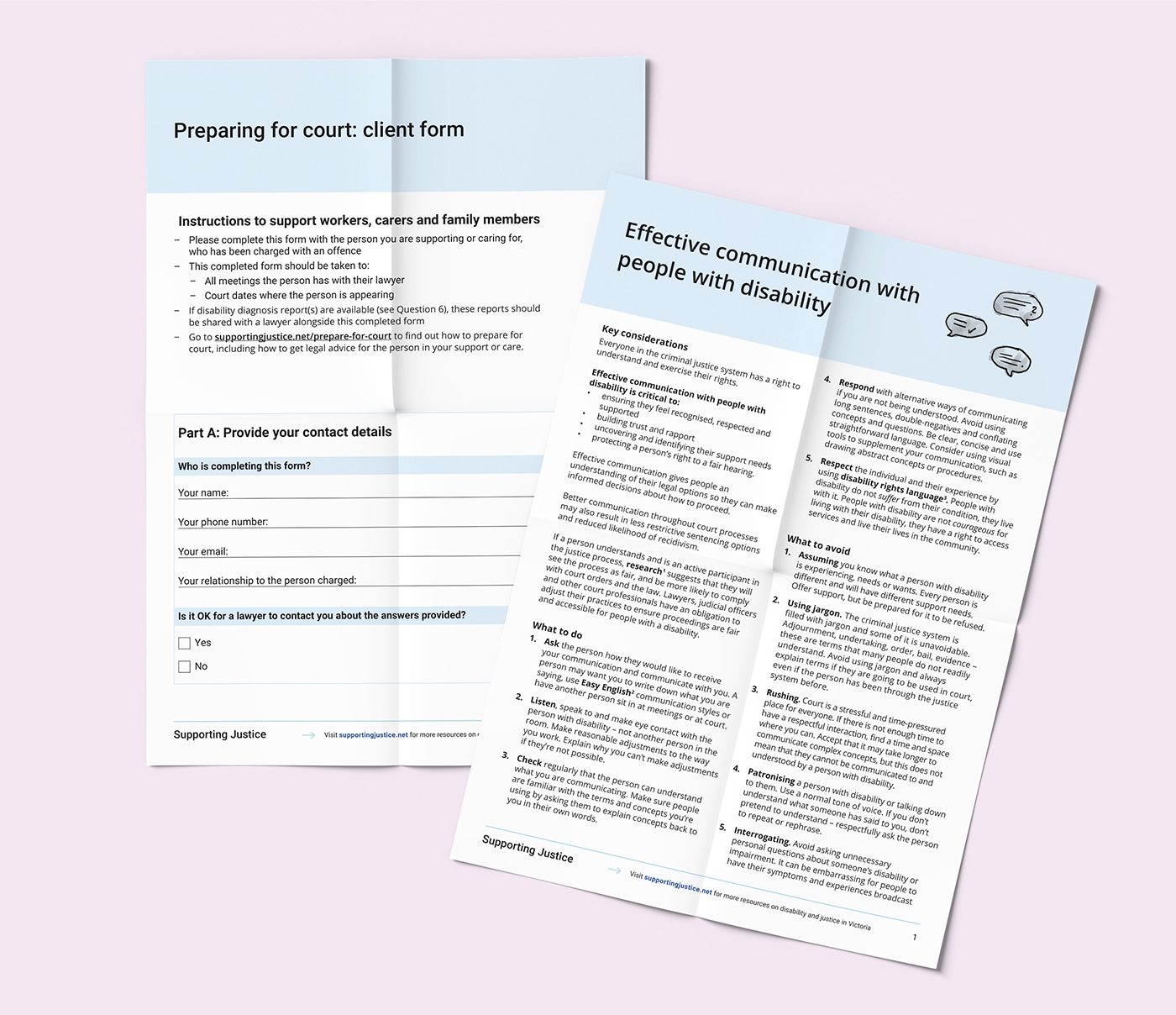

"It's OK to ask."

A big learning from project participants with lived experience was that they want lawyers and magistrates to ask them questions, to hear their needs, and to act accordingly. For example, duty lawyers can be ill-equipped to recognise signs of disability, reluctant to ask ‘prying’ questions for fear of offence, and are generally too time poor to sit with their clients, listen to their needs, and to recognise signs of disability that may change how their case is handled.

In response we facilitated the co-design of a guide to Effective communication with people with disability with people with lived experience, lawyers and peer support workers and advocates. The guide is for lawyers and magistrates to use when communicating with clients and defendants with disability so they can:

- make informed decisions about how to proceed

- have their right to a fair hearing upheld and protected

- have their support needs identified and addressed

- feel recognised, respected and supported by the system

Since this resource was debuted to magistrates at the Victorian Magistrates Convention in mid-2019, one magistrate reports he has started asking questions of the people coming before him, and finding out things he wouldn’t have, and that it has changed the way he has been sentencing people with disability.

Helping clients get the support they need

In response to knowing that lawyers are time poor and unable to spend adequate time to determine their client’s needs, we developed a Preparing for Court client form for distribution throughout the justice, housing and support network; anywhere that people with disability might come into contact with the justice system and require support.

The form is intentionally designed as a printable, accessible PDF. It was co-designed with people with lived experience, support workers and lawyers, and is formatted in Easy English.

The form is designed for supporters and carers to complete sitting together with a person with disability to ensure they are prepared for court. The contents of the form helps lawyers know more about the person’s background, living arrangements, instances of head trauma or violence, disability diagnoses, and other circumstances which may help their case, with the aim of upholding their rights in the court process.

Even if the form isn’t fully completed, just being given the form is a signal to lawyers that their client may have a disability, and that a file should be set up accordingly to handle their case.

Practical resources to build capability and improve outcomes

Acknowledging the need for improving the skill of legal and court professionals in recognising the signs of disability and acting accordingly, a multi-pronged approach was taken to resource development.

As well as the Effective communication with people with disability and Preparing for court resources, we developed:

- how-tos for legal and court professionals to clarify what to do in particular contexts such as preparing a plea or accessing the NDIS

- descriptions of signs of disability for legal and court professionals to be aware of

- service and program contact details for justice and disability support services

- a fully customisable version of Supporting Justice website content in slide form for use in training and workshops.

You can access these and other resources at supportingjustice.net.

I was surprised by the stories of those with lived experience and found it to be invaluable to discuss their experiences with us.

— Lawyer

Diverse voices, diverse needs

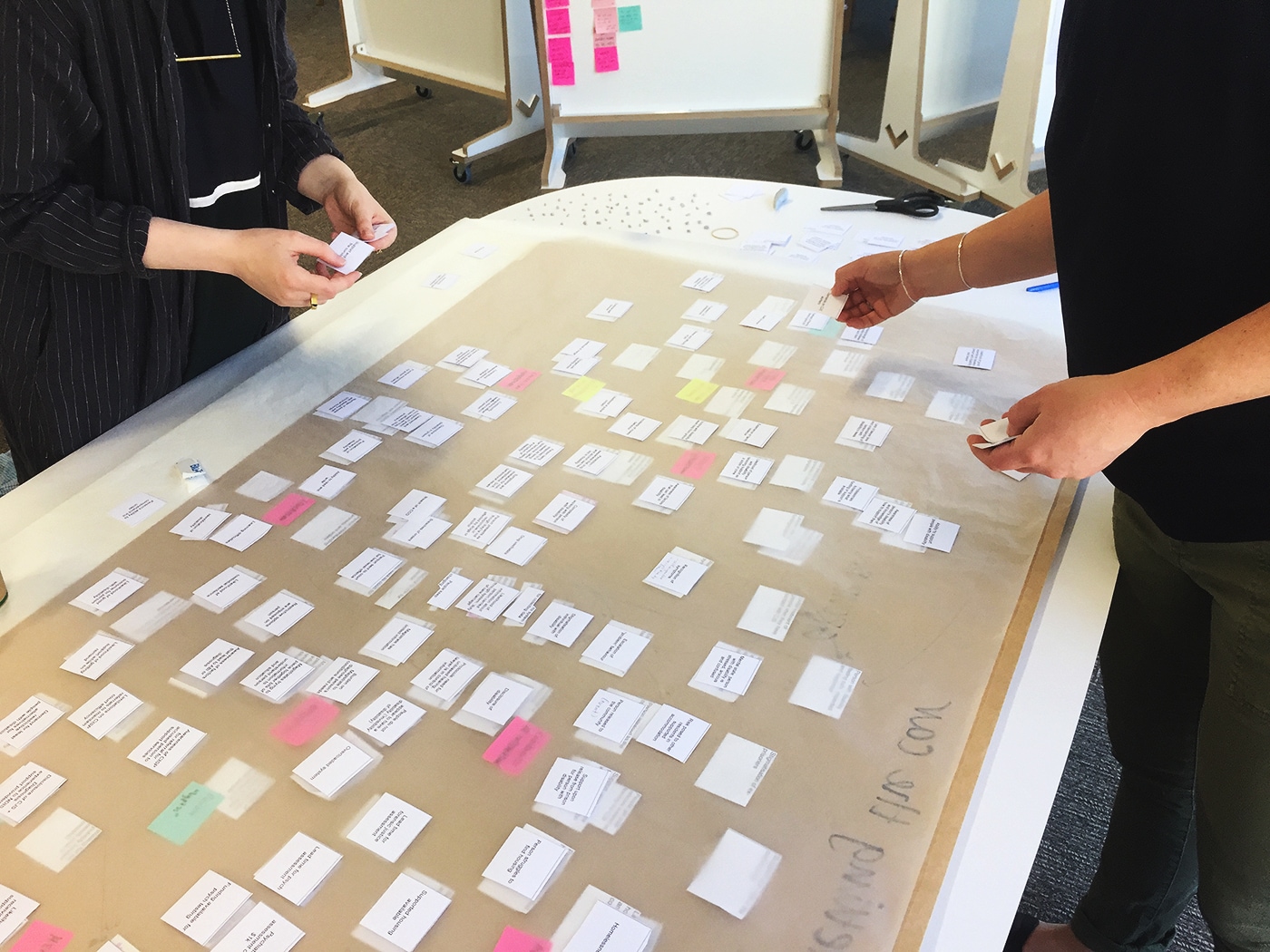

On multiple occasions the Supporting Justice project had people sitting side by side who would typically be separated by a bar, a bench, and centuries of hierarchical protocol.

Over three co-design workshops, 12 representatives from the legal profession, courts, the judiciary, the disability support and advocacy sector, and 4 people with lived experience, collectively generated ideas for change in the criminal justice system to improve outcomes for people with disability.

Justice stakeholders who attended stakeholder workshops found the co-design format very different to the reference and working groups that they were familiar with. Hearing first-hand from people with lived experience was compelling and confronting for some, confirming and sometimes amplifying what they knew of where the system is failing people with disability.

Some stakeholders are now taking active steps to be more inclusive in their working groups and strategic planning. For example, one agency has since sent its staff to Voice at the Table (VATT) advocacy training to build their inclusive practice capability.

(The co-design workshop) confirmed it’s fundamentally difficult for people to navigate the system with understanding, comprehension and feeling respected and fairly treated.

— Magistrate

(Co-design session learnings) emphasised some of the structural issues and difficulties that we all encountered providing services to the people that we’re running the program for.

— Policy/program manager, Department of Health and Human Services

Creating space for care

Bringing diverse participants together in a shared forum was challenging for everyone involved, from people with lived experience to magistrates.

We took particular care in how we invited and involved people with lived experience to these sessions. This meant liaising with participants’ peer support workers, including sending them session invitations in Easy English to pass on to participants, and communicating directly with participants through their preferred modes – phone, SMS or post – to remind them about sessions and conduct follow-up check-ins to see how they felt post-session and ask if they wanted any support.

Post-project evaluation found that despite these challenges, people connected with the project, and felt it was a genuine opportunity to participate in system reform.

I think you are doing a good job in this field. I hope people will pick it up and use what you design. I would like to offer my services if I can help further.

— Co-design workshop participant (with lived experience)