ArticlesApril 9th, 2020

If you landed in a foreign country with no documentation, could you prove who you are?

Citizen of Chin State, Myanmar, holding Citizenship Scrutiny Card. Photo credit: Chris Marmo / Paper Giant

How would you do it?

For this hypothetical, assume you don’t have internet banking or scans of your passport on Dropbox.

There are three traditional pillars of identity. The first is documents. The second is biometric — your appearance, your fingerprints, etc. This can only be used if a record of your biometrics is on file somewhere, which (thankfully) is uncommon. The third pillar is your life story, and in Western countries, it’s the pillar we are least aware of.

For an idea of how life story can demonstrate identity, look at the following two statements. Which one of these people is more likely to be from Sydney?

- “I got my first job at Woolworths when I was 15. I wanted money to buy clothes and stuff.”

- “I got my first job in a garment factory when I was 11. My family needed the money.”

Natural-born Australians think of their documents as the most important proof of their identity. Indeed, they may never need to use any other. But your passport can be stolen. Your lease agreement can be destroyed in a flood.

Your life story lives in your head and can never be taken from you.

Refugees coming to Australia have often lost everything except their life story. Persecuted ethnic minorities may have deliberately destroyed evidence of their ethnicity, to protect themselves. Or if they have documents, they are not ones natural-born Australians would recognise or know how to interpret. (Imagine turning up at the passport office with your birth certificate, your drivers’ licence and your most recent electricity bill. But the passport office isn’t interested in any of those documents. They want to see your fishing licence and your Year 10 school report. What do you mean, you don’t have them? Very suspicious.)

From 1962–2011, the Chin people of Myanmar were subject to severe violence and persecution by the ruling military junta. During this period, thousands of Chin refugees were accepted into Australia on temporary protection visas. Their refugee status is not in question, but to become citizens, they need to prove their identity.

Chin woman. Photo credit: Chris Marmo / Paper Giant

Strategic design studio Paper Giant conducted a 5-month ethnographic research project in Chin State, Myanmar, aimed at making it easier for Australian authorities to review the identity of Chin refugees who can’t fulfil the ‘100 points’ criteria. This will significantly speed up the process for Chin refugees and reduce the amount of time they spend in stressful citizenship limbo.

Over 6 weeks, our team of researchers, translators, fixers and drivers interviewed Chin people from urban and rural areas, old and young, day labourers, white collar workers and community leaders. We were looking to understand the common threads that can be found in people’s life stories, and what documents an ordinary person might be expected to have.

For example, in the same way that it’s not odd for an Australian not to have a fishing licence, it’s not odd for a Chin person not to have a birth certificate. However, most Chin households do have a Household Register, which records who is living in the house at various times.

We also looked into events that destroyed people’s ID documents, from Cyclone Nargis in 2008, to a fire at Falam Baptist College that damaged student records.

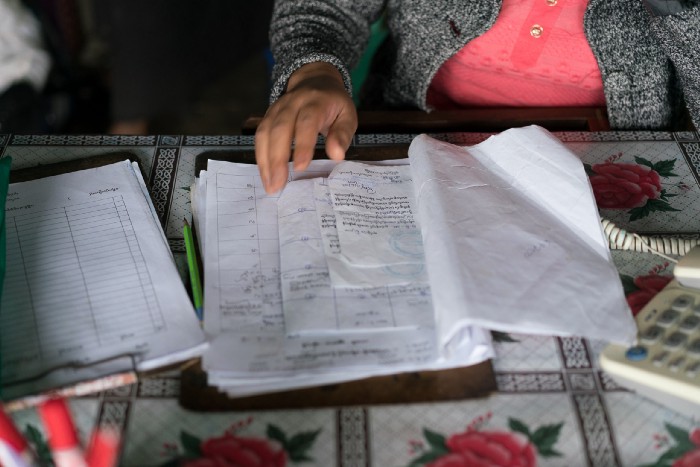

A research participant shows their family identity documents. Photo credit: Chris Marmo | Paper Giant

While everyone’s life story is different, there are cultural touchstones. For example, most Chin people first leave home at a young age to attend high school. Fathers are often absent for long stretches due to seasonal work. Even if an individual didn’t have these experiences themself, they would see them as normal.

To these markers of identity, we added another: place. A person who grew up in Melbourne should be able to describe what Flinders St Station looks like. A person who grew up in Hakha township in Chin State should be able to describe what the Hakha Baptist Church looks like. Memory of place, like life story, is a form of identity that cannot be taken from you.

We created a guide to Chin State that extensively documents infrastructure such as schools, health facilities and transport hubs in different villages and townships. We photographed landmarks and discovered the major local events people typically remembered and found significant.

Primary school students in Chin State. Photo credit: Chris Marmo | Paper Giant

We also discovered major cultural differences that could affect interactions between Chin refugees and Australian authorities, if not properly understood. Western culture tends to be pretty rigid in our naming conventions. Australians who change their name in adulthood often struggle to get the new name accepted by their peers. And if that name isn’t registered with the Department of Births, Deaths and Marriages, it won’t be seen as a ‘real’ name. In contrast, Chin people are often given multiple names. Their mum and dad might each have a different name for them. They might get another name in school, and another when they move to a new township. They aren’t changing names, they just have different names for different people and situations. It’s important that Australian authorities understand that this ‘inconsistency’ is perfectly normal.

The right to a separate personal identity is enshrined in the Declaration of Human Rights, but if you somehow end up outside the chain of verifiability, it becomes very hard to assert that right. Hopefully this research project will make it a little easier for Chin refugees.

Men gathered in a local restaurant after a church service. Photo credit: Chris Marmo | Paper Giant

Read more about this project from a design perspective:

‘Creating a world-first framework for assessing refugee identities’.