ArticlesNovember 1st, 2025

How Human-Centred Design Effects Systems Change

The beautiful service blueprint is complete. The journey map reveals every pain point. Your prototype tests brilliantly. Yet six months later, nothing has fundamentally changed.

Or perhaps you're approaching from another angle: you've mapped the system, identified the leverage points, understand what needs to shift. But your stakeholder consultations yield the same recycled ideas. Your pilot programs don't scale.

Whether you're a designer wondering if your work can create deeper impact, or a systems practitioner looking for methods that turn understanding into action, here's what we've learned at Paper Giant: human-centred design is powerful systems change practice.

But only when we deliberately wield it as one.

The Shift We Need to Make

Traditional design optimises existing systems: faster processes, clearer communication, smoother journeys. But what if streamlining a broken system just helps it discriminate more efficiently?

On the other hand, traditional systems change work identifies leverage points and intervention strategies without necessarily having a wider suite of methods and tools to shift it.

When we only improve experiences within broken systems, we make them more bearable and therefore more durable. When we only analyse systems without practical tools for transformation, insight doesn't become impact.

Human-centred design can bridge this gap. Design research reveals invisible dynamics; co-design redistributes power; prototyping makes abstract futures tangible. These aren't just service design tools or theoretical frameworks – they're practical methods for transformation.

A Framework for Systemic HCD

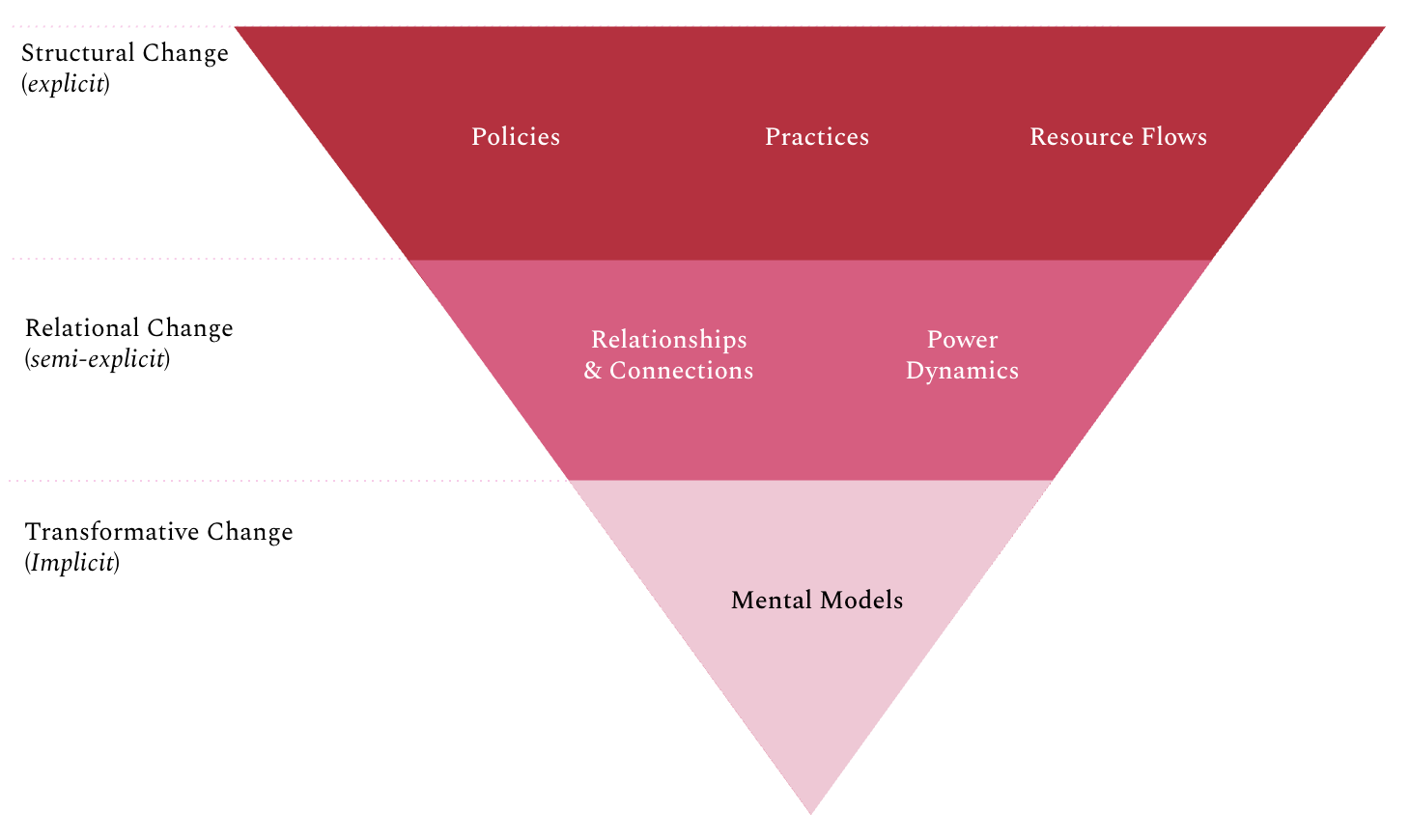

In our work this year, we've been applying the 'Waters of Change' model of system change, which identifies five conditions that hold problems in place: mental models, relationships, power dynamics, resource flows, and policies and practices.

The framework, developed by FSG, organises these conditions across three layers based on their visibility and transformative potential:

Structural conditions (explicit) are the most visible because they're formally documented and measurable—policies (the official rules and regulations), practices (how organisations actually do their work), and resource flows (where money, people, and knowledge go). We can easily point to these, count them, and track changes in them. But changes here rarely last on their own.

Relational conditions (semi-explicit) are less visible because they exist in the spaces between people and organisations rather than in formal documents. Relationships (the quality of connections between different groups) and power dynamics (who gets to make decisions and whose voice carries weight) shape everything above them. While we might sense these dynamics in a room or see their effects, they're rarely written down or openly acknowledged.

Transformative conditions (implicit) are the least visible because they exist in our minds as unconscious assumptions. Mental models—the deeply held beliefs about 'how things work' and 'what's possible'—drive all our decisions and behaviours. They're invisible because we rarely question or even recognise them; they're simply 'the way things are.' Yet without shifting these underlying beliefs, other changes won't stick.

The model emphasises that sustainable change requires working across all three layers. Surface-level structural changes will revert without addressing the relational dynamics and underlying mental models that maintain the status quo.

These conditions represent leverage points where HCD methods create transformation. Our existing toolkit, when aimed at these conditions rather than surface symptoms, becomes systems change practice.

Our recent work with the State Electricity Commission (SEC) on Consumer Energy Resources demonstrates how.

The 'Waters of Change' model of system change describes three laters: structural, relational and transformative change. Each layer can be the target of human-centred design interventions.

Policies and Practices: Changing the Rules

Written and unwritten rules often block innovation even when everyone agrees change is needed.

Journey mapping from the user's perspective reveals what policy reviews never capture: the cumulative burden of well-intentioned rules. Each department's reasonable requirement becomes part of an unreasonable whole. Service safaris take this further by having policy makers navigate their own systems as users do. The executive who spends a day trying to access their own organisation's services emerges with visceral understanding of regulatory burden.

But the real breakthrough comes from prototyping policy change in contained experiments. Instead of debating theoretical impacts, we can test modifications with real users in controlled conditions. What happens when we remove that verification step? When we trust rather than audit? When we simplify that form? Co-designing these experiments with both policy makers and implementers ensures changes are both ambitious and workable. The evidence from these prototypes does what no position paper could: it proves change is safe, beneficial, and practical.

Our SEC work uncovered a perfect example of policy blocking innovation: connection standards required household batteries to meet the same technical assessments as industrial generators, creating months-long waits for simple home installations. Once the systems map made this bottleneck visible to all stakeholders, SEC could advocate for specific, fit-for-purpose residential standards rather than general regulatory "reform."

Resource Flows: Redirecting Investment

Resources flow in patterns that reinforce existing systems. Changing these flows changes what's possible.

Service blueprinting reveals what spreadsheets hide: the true cost of complexity. When you map every touchpoint, every form, every back-office process, the waste becomes undeniable. That welfare application requiring five departments to process? The journey map shows it costs more to verify eligibility than to provide the benefit. But revealing inefficiency isn't enough to shift resources.

The power of design research is making the case through human impact, not just economics. When executives experience the prototype of a simplified service, when they hear directly from users about time lost to bureaucracy, when they see staff frustration mapped alongside customer pain points, the argument for reallocation becomes visceral. Co-design sessions surface another level of opportunity: resource sharing between organisations that didn't know they were duplicating efforts. The visual artifacts (maps, blueprints, prototypes) become business cases more compelling than any spreadsheet because they show both the current waste and the possible alternative.

The SEC mapping revealed exactly this kind of misalignment: households were investing in batteries for backup power while networks invested separately in grid infrastructure for stability. The visual systems map made clear how payment restructuring could align these investments, with households compensated for grid services, not just energy export, reducing infrastructure costs while making household investments more valuable.

Project Practices: The Hidden Systems Intervention

Repeated practices like weekly working sessions and regular showcases aren't just project management. They're systems interventions working across all conditions simultaneously.

These rituals create a different kind of change. Weekly sessions normalise uncertainty, teaching stakeholders that expertise means asking better questions, not having all answers. When participants regularly share unfinished work, vulnerability becomes strength. When facilitation rotates, hierarchy flattens. When decisions are made transparently each week, power redistribution becomes habit, not event. The repetition matters: stakeholders absorb design thinking through exposure, building confidence until they run these sessions independently. The ritual becomes the change.

In the SEC project, Thursday sessions always began with "what we heard," showing how last week's input had shaped the evolving map. By week three, participants were sketching additions themselves rather than just describing them. By week five, it had become "our map," not Paper Giant's. The ritual of collaborative mapping had built collective ownership.

Power Dynamics: Redistributing Agency

Who decides? Whose voice counts? Traditional consultation asks for input then decides elsewhere. HCD can genuinely redistribute power.

Power mapping makes the invisible visible, showing not just who sits where on the org chart but who actually influences decisions, who gets heard, who gets ignored. Journey analysis reveals something more visceral: the exact moments where people lose agency in systems meant to serve them. The unemployed person who must perform gratitude for inadequate services. The patient who cannot question the treatment plan. These moments of powerlessness compound into system-wide inequity.

Real power redistribution requires more than consultation. It requires handing over the tools of design itself. When communities learn journey mapping, they can document their own experiences without interpretation by outsiders. When they facilitate co-design sessions, they control which voices get heard. When they own the prototypes and research insights, they can advocate with evidence they created. The progression is deliberate: from participating in our research, to leading their own research, to not needing us at all. Each rotation of facilitation, each shared decision-making criteria, each capability-building session transfers actual power, not just the appearance of it.

With SEC, energy retailers initially participated carefully, protecting their positions. But the collaborative mapping process created a different dynamic. When retailers could add their operational constraints directly to the shared systems map, showing real challenges around grid stability, they moved from defensive to constructive participation. The power dynamic evolved from separate agendas to different perspectives on a shared challenge.

Relationships: Building Networks for Change

Systems are made of connections. These relationships determine what's possible.

The power of design research lies not just in mapping existing relationships but in revealing the gaps that keep systems stuck. Stakeholder mapping might show the formal structure, but journey mapping reveals the painful truth: the mother navigating disability services never actually speaks to the person designing those services. The frontline worker's insights never reach policy makers. These missing connections aren't oversights; they're structural features that preserve power dynamics.

Co-design creates relationships that shouldn't exist according to organisational charts. When we bring together people who only meet as adversaries in formal submissions, something shifts. Working side by side on prototypes, sharing sticky notes, sketching solutions together: these activities bypass professional defenses and create human connection. The artifacts themselves become crucial. A shared journey map or systems diagram gives former opponents a common language, a neutral territory where different perspectives can coexist without canceling each other out. These design artifacts become the foundation for ongoing collaboration long after the project ends.

The SEC project demonstrated this when energy distributors and consumer advocates, who historically met only as adversaries in regulatory hearings, discovered through collaborative mapping that they shared the same frustration: neither had real-time data about household energy patterns. This common ground transformed them from opponents to allies sketching data platform solutions together.

Mental Models: Making Beliefs Visible and Changeable

Mental models determine what we see as problems worth solving. They're invisible yet shape everything. For systems practitioners, you'll recognise these as the deepest level of system intervention. For designers, these are the assumptions that constrain every brief.

Ethnographic research excels at revealing these hidden beliefs because it studies behaviour in context, not just what people say they think. When researchers spend time observing how welfare officers actually process applications, they uncover the unconscious belief that complexity equals rigour, even when it creates barriers. Journey mapping exposes another layer: by tracing each step someone takes through a system, we see where "that's just how it is" moments reveal fixed assumptions about who deserves help, what's possible, or what's normal.

But surfacing mental models isn't enough. Transformation happens through experience, not argument. When we share stories from user research, a single parent's narrative about navigating services does what no statistic can: it replaces an abstract "service user" with a human being. Speculative design takes this further by prototyping alternative realities. What if welfare was a universal right? What if communities controlled their own services? By making these futures tangible through artifacts and experiences, we expand imagination beyond current constraints. Most powerfully, when stakeholders participate in creating these alternatives, they begin to believe change is possible.

In our work with the State Electricity Commission, energy retailers initially saw consumer solar as threats to grid stability. But during collaborative mapping sessions, when retailers understood that families were using battery storage to keep medical equipment running during outages, the fundamental assumption shifted. "These aren't system disruptors, they're distributed resilience assets" became the new narrative. The visual systems map reframed the entire conversation from control to orchestration.

From Service Design to Systems Design

Working across all five conditions requires understanding ourselves as catalysts, not heroes. Success isn't a beautiful blueprint but shifted conditions that persist after we leave.

The SEC project demonstrates this. Rather than designing a "better" energy system, we revealed conditions holding the current system in place. The collaborative mapping process didn't just document the system. It began changing it.

The Choice Is Ours

Human-centred design has always had the tools for systems change. The question isn't whether HCD can do systems change. It's whether we're brave enough to use it that way.

For designers: Are you willing to look beyond user satisfaction to system transformation? To measure success in shifted power, not just service improvements?

For systems practitioners: Are you ready to move beyond analysis to intervention? To use design methods not as add-ons but as core systems change practice?

When we aim HCD at the conditions that hold problems in place, not just symptoms, we become systems change practitioners. Whether you started as a designer or a systems thinker, the tools exist. The frameworks align. The only question is ambition.