NewslettersNovember 26th, 2019

PG #47: Data and consent – are designers dropping the ball?

Good design is often about asking the right questions. So when you hear ‘human-centred design’, you need to get more specific: Which humans? What human action, or relationship, or outcome?

I’ve been thinking about this a bit lately because of some work that Paper Giant is involved in around the consumer data rights legislation in Australia. The goal of the CDR is laudable – to give consumers of banking and energy services the right of consent over who has access to their data (such as their account information and smart meter data). The aim of legislation like the CDR is to make it possible for individuals to know who has access to information about them, to know what those people or organisations are using it for, and, crucially, to revoke that access.

In this example of human-centred design, we can ask:

-

__Which humans?__ Consumers of banking products (i.e. just about everyone) -

__What action?__ Informed consent over who has access to my data, and how they use it.

Which leads us to a reframe: ‘What if we designed explicitly for consent?’

Real consent is informed consent – meaning it is not enough for people to click ‘Yes’. They have to understand what they are saying yes to.

Have you ever actually read the terms and conditions on a website or digital service you’ve signed up to use? What exactly are you agreeing to when you tick the ‘I agree’ box?

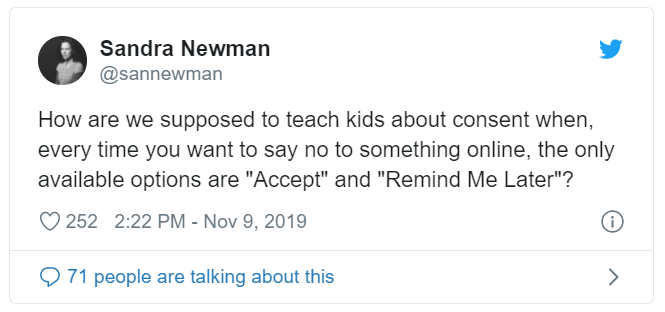

Informed consent is wilfully ignored by most software and service providers, because it benefits them to ignore it. Websites are designed to make it actively harder to know what you’re agreeing to. Often, the person ‘consenting’ is in the less powerful position. They may not actually have a choice at all, if they rely on the service, and it’s a case of ‘consent or be denied access’. It’s a classic case of ‘corporate-centred design’.

Fitness app Strava is an interesting example of a ‘consent first’ interface design: treating privacy like a nutrition label. Closer to home, Paper Giant recently had to think carefully about research consent processes while working with people with cognitive disability. We produced consent forms in Easy English and explained them in person to ensure that participants understood what we were asking of them.

I’ve only really talked about consent over data usage here, but you can quickly see how a simple reframe – ‘what if we designed explicitly for consent?’ – opens up new possibilities in how we think about design’s role in giving people the power to make decisions about their own lives and communities.